In the wake of terrorism against Black Americans in Charleston, beyond outraged and fed up, I compiled a list of race-related resources for fellow White Americans, who too often have the privilege to remain ignorant of the realities and toll of racism.

In the wake of terrorism against Black Americans in Charleston, beyond outraged and fed up, I compiled a list of race-related resources for fellow White Americans, who too often have the privilege to remain ignorant of the realities and toll of racism.

This Curriculum for White Americans to Educate Themselves on Race and Racism – from Ferguson to Charleston clearly struck a chord. The piece has been read and shared hundreds of thousands of times and been linked to by NPR, The Huffington Post and Teaching Tolerance.

And while most everyone with a website appreciates traffic to their work, an influx of visitors to mine has almost always meant that another Black American has been unjustly killed by the police or, more recently, White Supremacists have committed another act of terrorism, as they did not long ago in Charlottesville.

The thing is: while I have been teaching about issues of race and racism for nearly 20 years now, this viral curriculum is not actually my classroom curriculum, which was created for all students, not just white students. Students of a wide variety of racial backgrounds have cited this curriculum’s profound value in their lives.

In fact, when one white family tried to shut down the curriculum, students rallied to defend it.

Because I’m a better teacher than capitalist, I’m now making the curriculum available to the public in the form of a step-by-step guide. Following Charlottesville, I can no longer keep track of all of the great lists of resources out there, but far harder to find is a structured way of processing the wealth of information on these difficult topics. It requires guidance.

This guide, of course, is significantly modified for general, individual use. (Did you read that, trolls? This guide is only loosely based on my classroom curriculum and it has been “significantly modified.”) It can never replace the magic of the classroom, where transformative moments are driven not always by readings and videos but instead by discussions and connections to peers. (Educators: stayed tuned for a Teacher’s Guide.)

Before proceeding, I must acknowledge that this guide was initially heavily influenced by the work of Beverly Daniel Tatum, author of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations about Race, and Glenn Singleton, founder of the Pacific Education Group and creator of the Courageous Conversations protocol.

As I often stress, insights about race and racism rarely come from White Americans like me. While White Americans seem to disproportionately get praise and recognition for fighting racism, we are most often regurgitating the ideas and experiences of folks of Color.

Robin DiAngelo, a white woman who is one of the most prominent voices associated with antiracism, often tells her audiences that she has a Ph.D. in whiteness, to which Seattle writer and educator Reagan Jackson, who is Black, once messaged me, “me too, just not from an accredited institution.”

No matter how much research I do about race and racism, my privilege prevents me from ever fully understanding racism, certainly the oppression end of it. Through this guide, I try to amplify the voices of those who know far more than I ever will.

While anyone can benefit from the resources that make up this guide, I don’t deny that I make a concerted effort to keep White Americans reading. As I discuss later, this stubborn (but often loveable) demographic is the one that most often gets racism wrong. Generally, they are the ones who most need a guide.

Finally, despite its considerable length, consider this guide a primer, one likely to take in over an extended period of time. Here are the contents:

Step 1: Understand the Importance of Confronting Race Despite the Taboo of Race

Step 2: Understand Foundational Concepts: Race and Ethnicity

Step 3: (Begin to) Understand the Concept of White Privilege

Step 4: Understand the Historical Foundations of White Privilege

Step 5: Understand the Concept of Racism

Step 6: Explore a Case Study of Racism: The Criminal Justice System

Step 7: Understand the Importance of Intersectionality

Step 8: Understand Manifestations of Racism

Step 9: Immerse Yourself in Racial Identities

Step 10: Explore Ways to Fight and Heal from Racism

Step 11: Repeat These Steps Until Anti-Racist Action Is an Integral Part of Your Life

Pretty much every topic contains enough history and complexity to warrant a book. In fact, there are loads of books out there. I hope that this guide is just one step (well, 11 steps) of a much longer, book-filled journey, one that culminates in action.

Step 1: Understand the Importance of Confronting Race Despite the Taboo of Race

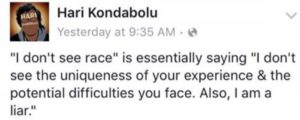

Since Trump’s rise has emboldened racists across the country, we don’t hear much about this country being “post-racial” anymore, a concept that dominated the media during the Obama administration. However, the idea of “colorblindness” – that being color conscious is problematic, that you “don’t see race” – was prevalent long before the Obama era, certainly among white circles. (After all, for folks of Color, it’s pretty tough to disregard the concept of race when you are reminded of your race regularly.)

Similarly, the taboo of race is primarily a white phenomenon. It’s not everybody who runs from the topic; in my experience, it’s disproportionately white people who do.

But then it’s also disproportionately White Americans who get racism wrong.

A recent survey reveals that a startling number of White Americans – 55% – believe that they are the targets of discrimination. Other studies (here and here) have corroborated the results of this survey.

The evidence simply doesn’t support these perceptions. In fact, few white respondents said they actually experienced the discrimination.

The evidence simply doesn’t support these perceptions. In fact, few white respondents said they actually experienced the discrimination.

So drop “colorblindness” (which is arguably an ableist term anyway). Disregard the taboo. It’s time for a new strategy.

The first step is committing to dive deep into race.

Before we do, a few words about intersectionality, which stresses the interconnectedness of our overlapping identities.

I of course value intersectionality and have a section devoted to the concept later. At the same time, over the years I have found that White Americans will go to superhuman lengths to avoid, stifle, subvert, and derail the topic of race.

Precisely because of the taboo of race, I feel strongly that there are times we need to isolate race. Otherwise, as Glenn Singleton asserts, we will never understand the profound role that race plays.

Isolating race will likely be profoundly uncomfortable. But isn’t that nearly always true of life’s most important lessons?

In the classroom, I invest a great deal of time establishing norms for discussing race (not to mention establishing a safe classroom). Since you are likely reading this alone, here’s one norm to consider, based on the work of Özlem Sensoy and Robin DiAngelo: “Notice your own defensive reactions and attempt to use these reactions as entry points for gaining deeper self-knowledge, rather than as a rationale for closing off.”

Here are some resources that show why the discomfort, including possible defensiveness, is worth it.

Color blind or color brave? by Mellody Hobson from TED Talk:

Why Color Blindness Will NOT End Racism, from MTV’s Decoded:

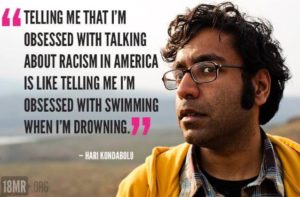

I took my stab at challenging “Colorblindness” in 7 Reasons Why ‘Colorblindness’ Contributes to Racism Instead of Solves It, but Hari Kondabolu does so far better in a fraction of the word count:

In short, if we want to eradicate racism, we have to confront race.

Step 2: Understand the Foundational Concepts of Race and Ethnicity

Take a moment and think about the stereotypes you have learned about various racial groups. Yes, it’s uncomfortable. You don’t necessarily have to believe them to include them on your mental list.

No, really. Stop reading and list a few before moving on to the next paragraph.

Which ones came to mind? That Black Americans are better at sports? That Asian Americans are better at math? That White Americans can’t dance?

Whether we believe them or not, we can all rattle them off.

But here’s the good news: science confirms that there is no biological basis to these racial stereotypes.

If that’s true, then what exactly is race?

Beverly Daniel Tatum cites Van Den Berghe in defining race: “ a group that is socially defined but on the basis of physical criteria,” such as skin color, eye shape, and hair.

And this definition is critical, as it forces us – from the very start of this journey into race – to confront, question, and challenge the stereotypes that we have internalized. And while Tatum cited this definition back in 1997, science has consistently supported it.

Basically, the genetic differences that account for differences in the way we look are as insignificant as, say, blood or fingerprint type. Could you imagine if we sorted and stereotyped people based on our fingerprints?

PBS’s RACE: Power of an Illusion, “The Difference Between Us,” does a great job not just explaining that race is a social construction without biological basis but also revealing the many failed attempts to find science that accounts for race:

Unfortunately, the full episode is no longer available online, but this short one by Vox does the job:

Armed with some history, you almost don’t even need the science. The categories for race have been fluid since their invention; they have been far more connected to power than science. More on this point later.

When you read words like “race isn’t real,” Just remember one message that RACE: Power of an Illusion is very clear about: though race may be an illusion, racism is most certainly not.

Now that we get race, what about ethnicity?

Race and ethnicity are often used interchangeably, but there is a distinction. Tatum defines ethnic group as “a socially constructed notion based on cultural criteria.” According to Singleton, culture is composed of many criteria, including ancestry, language, values, traditions, ceremonies, manner of dress, and more.

The distinction has significance. For one, it helps explain the Census’s handling of the “Hispanic” identity, which the government has treated as an ethnicity, not a race. Someone could be Latinx but be pretty much any race, from the very light-skinned stars of telenovelas to the many stars who we might have initially read as simply Black.

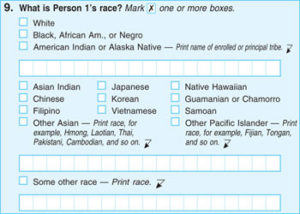

Franchesca Ramsey and Kat Lazo discuss the complexities of the U.S. Census below (as does this episode of NPR’s Code Switch podcast):

The understanding of ethnicity is particularly helpful when working with White Americans, many of whom confuse ancestry with ethnicity. For example, I know I have ancestry in Hungary but I know absolutely nothing about the country – I couldn’t even fill a thimble with what I know. To call myself culturally Hungarian – or even Hungarian American – would be flat out untrue. And too often white people use this misunderstanding of ethnicity to avoid labeling their race: white.

And this is the power of studying race, especially for those who have the privilege not to think about their race. Once you put race on the table, even White Americans have to admit that they too have a race. And once they admit that, they invariably have to ponder why it is that they have had to think so little about it.

And that leads us to step three: White Privilege.

But before we move there, it’s important to acknowledge that the categories of race and ethnicity are full of complexities. Just look at the 2010 Census:

Some of the categories are based on countries, some on regions, and some on colors (of course, some colors you absolutely avoid today). And you can be still be an “other” in 2010.

Yet, as inconsistent at these categories can be, they are still important. For one, they are intimately tied to the identities of many. When asked what he appreciated about this race, one multiracial student I taught responded, “My race is everything.”

These categories are also important because they help us track racial disparities. (More on disparities later.) Without them, we would never know if we as a community are meeting the needs of everyone.

Step 3: (Begin to) Understand the Concept of White Privilege

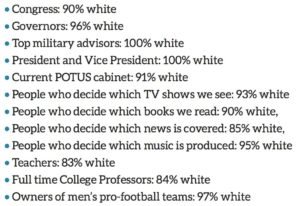

Here’s a paradox: White dominates the culture, from our government leaders to our professors to our media stars. Yet – for the most part, for too many White Americans – whiteness remains unexamined.

What does it mean to be white? Let’s have that discussion!

As a starting point in class, I often show White Like Me, in which Eddie Murphy, through a Saturday Night Live mockumentary from 1984, experiences New York City as a white man:

While the skit is limited in its black/white binary approach, how much truth does it hold?

Perhaps the most famous text on the topic is “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” by Peggy McIntosh, a white professor at Wellesley College. I am reluctant to assign it because, as I mentioned, these ideas do not come from white people. Before McIntosh, literally millions and millions of people of Color could have told you that white people have unfair advantages.

Despite my reservations, read White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. Click away.

If these ideas are new to you, please read it again.

One of the reasons McIntosh’s piece is so powerful is that it rings true for most of us even without much hard data, which, at this point, is what we want. The hope right now is to engage at an emotional level. We can get all heady with numbers later (and we will).

Here’s perhaps the most powerful five-minute testimony on the power of White Privilege, from The Color of Fear, a film I encourage you to watch in its entirety:

Still not convinced about the power and prevalence of White Privilege? Not long ago, I wrote a piece that updated McIntosh’s work, except with one key distinction; I explicitly credited the many people of Color who taught me about White Privilege’s power and prevalence: 10 Examples That Prove White Privilege Protects White People in Every Aspect Imaginable (a title, for the record, that I did not choose)

I’m currently compiling resources to learn about White Privilege exclusively from people of Color. Here’s a good one from ArchDuke that even manages to include some humor.

For many folks of Color, this step may seem obvious and many will be quickly ready to move on to step four.

For many White Americans, this step is the hardest.

Fortunately, the Black Lives Matter movement and resources like Everyday Feminism have helped push the concept into mainstream discourse, so hopefully this guide is hardly the first time you have encountered the concept of White Privilege. When you can watch Jon Stewart and Bill O’Reilly debate the topic on The Daily Show in the wake of outrage in Ferguson, you know that something has shifted.

Nevertheless, if you are new to the concept of White Privilege, please don’t think you got it after reading an article. One example that McIntosh left off her list: I have the privilege to forget about my White Privilege. For white people at least, this is a lifelong process, full of inevitable fuck ups but also of epiphanies.

And if you did watch the Eddie Murphy clip, watch Racism is Real and ask yourself: Is the SNL skit in which white people get free stuff really that satirical?

Step 4: Understand the Historical Foundations of White Privilege

The existence of White Privilege is not an opinion held by some radical teacher. Even a “little research” convinced Megan Kelly that it’s real.

So let’s do more than a little research and dig into some history. Here are some entry points:

- If Anyone Ever Questioned How White Privilege Manifested Itself in America This Is The Perfect Illustration, from Atlanta Black Star

- 8 Times the U.S. Government Gave White People Handouts to Get Ahead, from Atlanta Black Star

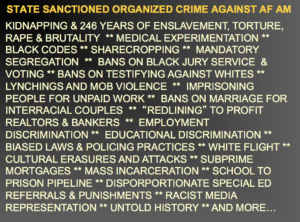

Maybe Americans, especially White Americans, wouldn’t get racism so wrong if the following sampling of cases/policies, beyond the commonly cited systems of slavery and Jim Crow, were common knowledge.

In each of the following, ask the question, “Which race benefitted the most?” (Definitions of most of the following can be found on the Different Rules for Whites timeline of PBS’s Power of an Illusion website and the Sites of Shame timeline of the Denshō website).

- The Naturalization Act (1790), which restricted who could naturalize to whites only

- The Indian Removal Act (1830), which forcibly removed thousands of Natives east of the Mississippi to Oklahoma (an action that violated a Supreme Court decision)

- The People v. Hall (1854), which prohibited “aliens” in California from owning or leasing land and was applied exclusively to Asian immigrants

- Dred Scott Decision (1857), which is described powerfully by Melissa Harris-Perry below:

- The Homestead Act (1862), which allowed citizens to claim 160 acres of land mostly west of the Mississippi, encouraging invasion into Native lands

- The Dawes Act (1877), which broke up reservations in favor of smaller tracts of private property and resulted in the loss of millions of acres of Native land and the erosion of communal culture on reservations

- The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), which effectively ended Chinese immigration for the next 60 years and denied naturalization rights to Chinese immigrants

- Alien Land Law (1913), which were a series of state laws passed over subsequent decades that prohibited “aliens” from owning or leasing land, initially applied exclusively to Asian immigrants giving white farmers the competitive advantage

- Johnson-Reed Act (1924), which created immigration quotas that favored “Nordics” over “inferior races”

- Social Security Act (1935), which provided Social Security to all except agricultural and domestic workers, who were disproportionately Black Americans, Mexican Americans, and Asian Americans

- The Wagner Act (1935), which guaranteed workers’ rights but did not prohibit unions from discriminating based on race, keeping many workers of Color from receiving these rights

- The G.I. Bill (1944), a series of federal programs that helped veterans “attend college, receive job training, start businesses, and purchase homes,” programs that overwhelmingly went to white veterans

- Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1988), which imposed much harsher penalties for crack cocaine convictions, disproportionately used by Black Americans, than for powder cocaine, disproportionately used by White Americans

Of course, many White Americans will likely retort, “What about affirmative action?” Well, that’s a moot question in my state, which, following California’s lead, outlawed affirmative action in 1998. But research (try here, here, and here for starters) has consistently confirmed the biggest beneficiaries of affirmative action: white women.

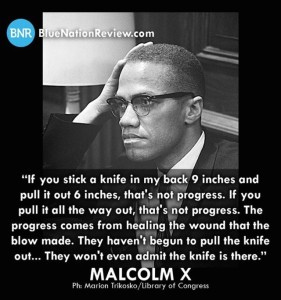

Many White Americans will also point to history to (try to) refute White Privilege. “Slavery ended forever ago,” they say. “Get over it,” they say.

But history matters.

In the classroom, I often use this country’s housing practices as case study to prove how much history matters. And by “housing practices,” I’m not even referring to the explicitly racist racial restrictive covenants that kept people of Color out of neighborhoods. And I’m not referring to sundown towns that dotted the landscape across the Midwest.

I’m referring to the “government engineered” policies, such as redlining, that have led to today’s deeply segregated country. Historian Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law, covers many of them in this must-listen 30-minute interview.

Because of these policies, most people of Color were kept out of housing markets that appreciated astronomically for decades before they were legally able to buy. By that time, they were priced out of the right to buy, which is why Rothstein calls it an “empty right.”

This history, relatively recent history, helps explain today’s egregious wealth disparities:

A remedy requires more than reversing discriminatory laws. After all, White Americans’ homes, initially bought at $7,000-$9,000, have appreciated $200,000-$500,000 (or more) due to federal policy.

To truly remedy this history, doesn’t that mean America must do the same for all those people of Color who were kept out of the government-subsidized housing market?

PBS’s RACE: Power of an Illusion, The House We Live In, is another great resource for this history, though the full episode is no longer available online. This history helps fuel Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Case for Reparations.

Step 5: Understand the Concept of Racism

Like digging into the concept of White Privilege, here’s another step that many White American’s don’t like: defining racism. Well, depending on the definition that you use.

Most of us have learned a variation of the same definition, one that likely matches the Microsoft Word dictionary’s definition: “animosity toward other races” and “belief in racial superiority.”

In this mainstream definition, anyone can be racist. Perhaps that’s why it has been so utterly embraced by the mainstream.

But we have already established that White Americans are advantaged in ways that most others are not. Shouldn’t the definition of racism capture that reality?

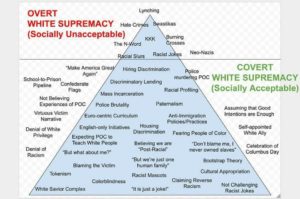

More might agree except for one major barrier: White Americans, generally speaking, are petrified of the words “racism” and “racist.” To too many, they associate these terms with the most egregious and overt forms of racism: the KKK, white sheets, burning crosses, increasingly (where I live) Donald Trump.

Here’s the problem with those associations: if White Americans exclusively associate racism with manifestations of hate, then they will never want to own their own racism. And owning your racism is a critical early step in the fight against racism.

Thus, paradoxically, white people’s fear of racism can actually protect racism.

It’s critical to sever these associations. As Beverly Daniel Tatum argues, racism is like smog. It’s everywhere; we are all breathing it in. Thus, I encourage my students to cut themselves slack when it comes to the racism that they’ve internalized.

As I write in one of my pieces on this topic, “…if you have internalized racist ideas, it doesn’t mean you are bad; it means you watched Peter Pan as a kid (or the thousands of other biased films and television shows). It means you were likely raised by folks who too fled racism.” (On the topic of media, here’s one thorough (and humorous) take-down of media’s blatant racism: Hollywood Whitewashing: How Is This Still a Thing?)

So back to the definition of racism. Many social justice folks prefer this one: prejudice plus power. Case in point – 5 Things You Should Know About Racism, from MTV’s Decoded:

Beverly Daniel Tatum finds flaws with this definition, in part because the power of White Privilege is the ability to render privilege invisible. In other words, White Americans don’t necessarily feel their power, at least not without some education.

Instead, Tatum cites author David Wellman in defining racism as a “system of advantage based on race.” In the United States, it would hardly be a stretch to call it a system that advantages white people.

Of course, White Americans generally buck at the major implication of this definition – that only white people can be racist – often pointing to that one time someone called them a racial slur. Yes, people of Color can be discriminatory toward white people. The difference is that people of Color are not backed by an entire system.

I refute the misconception that white people face such systemic discrimination here:

“Is it possible that a White American remains stuck in concentrated poverty because of their race, gets targeted by the police because of their race, gets a shitty education because of their race, can’t get a fair shot at a top university because of their race, can’t get a fair shake at a good job because of their race, can’t get access to good housing or health care because of their race, and can’t find anything to watch aside from Empire, Fresh Off the Boat, Master of None, and Luke Cage?

I suppose anything is possible, but it sure as hell doesn’t seem likely.”

This video by Mic, We All Have Racial Bias, explores the complexities of the definition of racism well (again with some humor):

Given that White Americans are so often trained that being racist is the worst crime ever, it’s no surprise that many struggle with Wellman’s definition. But remember: racism is huge. The City of Seattle makes distinctions between individual/interpersonal, institutional, and structural racism.

Institutional racism is defined as the “policies, practice, and procedures that work to the benefit of white people and the detriment of people of color, usually unintentionally or inadvertently,” while structural racism is defined as the “interplay” of multiple institutions that leads to “adverse outcomes and conditions for communities of color.”

Racism is much bigger than any individual. That doesn’t mean we as individuals are off the hook, but it does mean that white people can put their defensiveness down. The call to confront racism is not a personal attack.

Whether or not you agree with the Wellman definition (which is much easier to remember than Seattle’s multiple definitions), the data all support that there is indeed a system of advantage based on race. Here are a few resources that provide overwhelming evidence:

- Here’s Your Proof that White Americans Don’t Face System Racism, from Everyday Feminism

- The Ultimate White Privilege Statistics and Data Post, from The New Progressive

- What is Systemic Racism? video series, from Race Forward

- Yes, You Can Measure White Privilege, from The Root

- 7 Ways We Know Systemic Racism is Real, from Ben and Jerry’s

In No, I Won’t Stop Saying White Supremacy, Robin DiAngelo uses “White Supremacy” because the term, as loaded as it is, shifts the problem of racism to White Americans instead of treating it as a problem for people of Color. Especially since Charlottesville, I have noticed an uptick in the use of “White Supremacy” when referring to racism, so perhaps the Wellman definition, in comparison, won’t remain so hard for White Americans to swallow.

While I promised to highlight the work of folks of Color, this 22-minute primer by DiAngelo on racism is simply too good to omit:

Step 6: Explore a Case Study of Racism: The Criminal Justice System

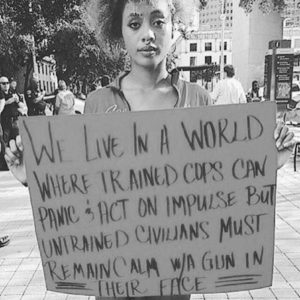

Protests targeting state violence against people of Color, most often Native and Black Americans, has spurred a civil rights movement, this time one not relegated to a history book.

If the killing by police is ever going to stop, if police are ever going to be held accountable, more people need to get involved. In the greater Seattle area alone, police killed three people of Color – Tommy Le, Charleena Lyles, and Giovonn Joseph-McDade – all within one month, all with too many questions unanswered.

Perhaps the most powerful resource on this topic is Ava DuVernay’s 13th, available on Netflix. Start with 13th, if you haven’t already watched it, but be warned: there’s no trigger or content warning that can fully prepare some for this film. Take care of yourself. Here’s the trailer:

But I’d be remiss if I didn’t include other voices who have been pivotal in bringing the injustice of the criminal “justice” system to our consciousness.

Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow:

Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative:

Ta-Nehisi Coates, writer for The Atlantic and author of Between the World and Me:

There is an overwhelming body of writing about our criminal justice system. I will not even try to link to them all. I will, however, link to 18 Examples of Racism in the Criminal Legal System, which demonstrates racial bias in all of the following areas:

- Police Stops

- Police Searches

- Police Use of Force During Arrest

- Juvenile Arrests

- Arrests in the Transgender Community

- Arrests for Drugs

- Police Arrests for Marijuana

- Pre-Trial Release

- Prosecution Charges

- Prison vs. Community Service

- Length of Incarceration

- State Drug Incarceration

- Federal Drug Convictions

- Federal Court Sentencing

- Incarceration of Women

- Sentencing to Life without Parole

- Hiring People with Criminal Records

- Eliminating the Right to Vote

Despite the depth of these issues, there are solutions. Here is a place to start:

- Solutions for Police Brutality by Shaun King, a 25-part series from The New York Daily News

- We Already Know How to Reduce Police Racism and Violence, from Yes! Magazine

Step 7: Understand the Importance of Intersectionality

The topic of police violence against communities of Color allows an opportunity to discuss intersectionality, a term coined by legal scholar and critical theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how “different forms of discrimination can interact and overlap.”

When police target communities of Color, too often cis male victims are the ones who receive media coverage and public outrage, a point Crenshaw makes at the outset of this primer on intersectionality:

While masses of people have demanded that our feminism be intersectional, for whatever reason, the movement for racial justice has not faced the same pressure, at least in my experience. For example, I have yet to encounter the term “intersectional anti-racist.”

Nevertheless, I have indeed noticed an increased emphasis on intersectionality in the movement for racial justice. Here are a couple examples:

- #RaceAnd Video Series, from Colorlines

- Dear Latinx, Lets Check Our Privilege, from Thee Katz Meoww (below):

Like history, intersectionality matters. Attacks against immigrant rights often result from the intersection of racism and xenophobia. Here are resources to set the record straight on immigration:

- Busting The Biggest Immigration Myths In America, from AJ+ (below):

- Immigrant voices make democracy stronger, by Sayu Bhojwani from TED Talk

- Ten Myths About Immigration, from Teaching Tolerance

Similarly, Islamophobia, skyrocketing since the rise of Donald Trump, results from the intersection of racism and religious oppression. Here are some valuable resources on Muslim American experiences:

-

- Mic Op-Ed: These Muslim kids are standing up to Islamophobia, from Mic

- Muslim School Children Bullied By Fellow Students and Teachers, from NPR’s Code Switch

- US Muslims: Survey suggests nearly half suffer discrimination, from The BBC

- Dear Hollywood: stop portraying Muslims as terrorists, from Vox (below):

Though I argue that there are times we need to isolate race, there’s no arguing with self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” Audre Lorde:

“There is no thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

Step 8: Understand Manifestations of Racism

Bryan Stevenson argues that slavery never ended; it evolved. The same can be said for racism.

Fortunately, there is vocabulary to discuss the complexities and nuances of racism, much of which had not entered the mainstream when I began teaching about race. Note that the following list is hardly comprehensive; racism is simply too big. But this list is an important place to start, especially when so much of racism works at an unconscious level.

Implicit Bias

Perhaps the best explanation of implicit bias is the following, an engaging lecture by one of the leading scholars on the topic, Anthony Greenwald:

You can think of implicit biases as the thoughts about people that “you didn’t know you had.” Wired defines this bias as “an unconscious but measurable response.” Such bias has been well documented in health care, education, policing, and many more areas – arguably all of them.

Think back to the video from step three, Racism is Real. It’s highly unlikely that those disparities result from conscious, explicit racism.

Furthermore, if you teleported all the white supremacists, whose biases are quite explicit, out of the country, would the system really fundamentally change? (A question I pulled from the Tyree Scott Freedom School.)

I don’t think so. Remember the smog? Just a tiny fraction of the pollution comes from outright white supremacists. Rather, it’s arguably implicit bias, combined with colorblindness, that allows systems to function without examination of their costs to various racial groups.

That’s why I spend so much of my time fighting for the study of race in public education. Without formal education, people could live their entire lives with their biases buried deep under the topsoil of their consciousness.

For the time being, Project Implicit provides Implicit Association Tests that help you bring some sunlight to the biases you didn’t know you had. MTV, producers of the Decoded series (yes, old timers, MTV), just released a seven-day “bias cleanse” (but I have yet to take it for a spin for you).

Unchecked, these biases could lead to a whole lot of the next manifestation of racism: microaggressions.

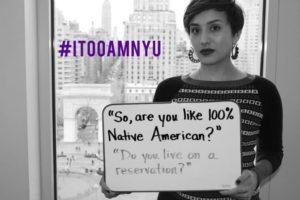

Microaggressions

Racial microaggressions are defined as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color.”

Here are a couple resources on microaggressions that I have found useful in the classroom. Notice that not all microaggressions are racial, but let’s keep the focus on race for three more steps.

#HatchKids Discuss Microaggressions, from SheKnows:

How microaggressions are like mosquito bites, from Fusion:

Microaggressions occur in classrooms, college campuses, workplaces, public spaces, movies – basically everywhere.

They are so common that Boldly responded with a humorous “If (insert group of Color) Said The Stuff White People Said” series, such as If Latinos Said The Stuff White People Say. (And if you are white and don’t find them funny, are you having a defensive reaction? Is something deeper going on than a difference in sense of humor?)

But before you can stop committing microaggressions, you have to understand what they are and how they impact those who have to deal with them.

Colorism

Lori L. Tharps, author of Same Family, Different Colors, defines colorism as “the privileging of light skin over dark” and credits Alice Walker for naming the concept (a name your computer dictionary will unlikely recognize).

Colorism is why companies profit from selling skin lightening creams world-wide ($400 million in India alone in 2013). Colorism, combined with implicit bias, helps explain why light-skinned people have higher incomes and shorter prison sentences than dark-skinned people. It explains why too many of the evil characters in video games and cartoons have darker skin than the heroes.

Colorism is why it takes campaigns – Dark and Beautiful and #UnfairandLovely – to help many dark-skinned South Asians feel beautiful.

Resources on colorism are increasingly common, including two documentaries (Dark Girls and Light Girls). For a shorter primer, check out this powerful student documentary directed by Kiri Davis:

And while many of the above examples have targeted South Asian and Black women, you can find stories of colorism in other communities as well, as demonstrated by 11 Examples of Light Skin Privilege in the Latino Community.

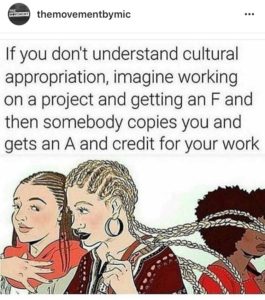

Cultural Appropriation

Maisha Z. Johnson defines cultural appropriation as a power dynamic in which members of a dominant culture take elements from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by that dominant group.” (Read Johnson’s full explanation here.)

Maisha Z. Johnson defines cultural appropriation as a power dynamic in which members of a dominant culture take elements from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by that dominant group.” (Read Johnson’s full explanation here.)

What’s particularly insidious about cultural appropriation is that the dominant group – white people, with a racial lens – too often receive praise for their dreadlocks, for example, while the folks of Color they are copying too often face discrimination.

And that fact is what separates cultural appropriation from, say, buying art during your vacation to wherever. In buying art, both groups – the artist and art consumer – benefit, a stark contrast from the examples Amandla Stenberg critiques:

There is a wealth of resources on the topic. Here are a few:

- Cultural Appropriation Is, In Fact, Indefensible, from NPR’s Code Switch

- Novelist Beautifully Destroys Those Who Don’t Believe in Cultural Appropriation, from NextShark

- What Distinguishes Cultural Exchange from Cultural Appropriation?, from The New York Times

And, yes, white readers, even folks of Color are held accountable when they take from cultures that are not theirs, as Kerry Washington learned after calling Kate Winslet her “spirit animal.”

Revisiting the Definition of Racism

Let’s revisit the Wellman definition of racism that so many white people struggle with, the one that says that, though anyone can discriminate, only white people can be racist: a system of advantage based on race.

Of these four concrete manifestations of racism – implicit bias, microaggressions, colorism, cultural appropriation – which ones support the Wellman definition?

Arguably, they all do. By definition, colorism and cultural appropriation certainly do. And while anyone can internalize implicit biases about any racial group, how many negative impact biases actually target White Americans? How many microaggressions actually target White Americans?

And while anyone can take from other cultures, white people overwhelmingly seem to be the perpetrators. And white people are the ones who have the power to mainstream culturally appropriation, as certain sports teams perpetually remind us.

So you can deny the Wellman definition, but doing so means ignoring volumes of evidence, evidence that makes the concept of reverse racism an impossibility. ‘Reverse Racism’ Is a Giant Lie‘ makes the case here:

In the following slide, Robin DiAngelo takes a similar approach to explain the reality that Black Americans have never had the power to do to White Americans what White Americans have done – and continue to do – to Black Americans:

And that’s not just true for Black Americans but for any group of Color throughout United States history. Comedian Aamer Rahman dismantles the argument of reverse racism brilliantly here:

Finally, Sherman Alexie shows how counterproductive it is for White Americans to use the term “reverse racism” to explain the discrimination they supposedly face.

Step 9: Immerse Yourself in Racial Identities

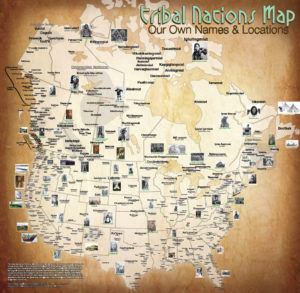

The New York Times’ 25 Mini-Films for Exploring Race, Bias and Identity With Students and other sources have made it unbelievably easy to gain insight into the experiences of other races. Each racial group has its own unique experiences and there is much to learn, especially when the categories we use are umbrella terms the don’t begin to capture the diversity found within, a point this map demonstrates:

But this step isn’t just about studying the identities of others. It’s also about your own journey.

Who exactly are you – racially?

The study of your own racial identity development, as Dr. Sandra “Chap” Chapman says, “helps us to make sense of the journey that we’re on.” It can also play an important role in accepting yourself and developing an anti-racist identity.

Before you start clicking, know that these links are hardly comprehensive. As with so much in this guide, they are starting points. Many focus on experiences of oppression, but remember that every group of Color has sources of pride and reasons to celebrate their identities – whether or not I could locate such a link.

If you know of resources to add, please include them in the comments.

- Asian American and Pacific Islander Identity

- Black American Identity

- Latinx American Identity

- Multiracial Identity

- Native American Identity

- White American Identity

Step 10: Explore Ways to Fight and Heal from Racism

Thus far, nine steps, for the most part, have targeted the problem of racism. Now is the time for the solution: action!

While I’m no expert on solving racism, I feel confident asserting that the movement for racial justice will most certainly entail significant discomfort and resistance from white people. In fact, you’ll be able to measure your impact by the amount of white pushback you receive.

And that resistance will come because remedying racism ultimately entails a redistribution of resources.

There are now more resources than ever to guide you in your work. Note that some of links directly below were written specifically for people of Color. A section specifically for White Americans follows.

As I mention in the introduction, there are many books on the topic of fighting and healing from racism, like the must-read Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome by Dr. Joy DeGruy, who some of you might have met through this clip about challenging racism in a check-out line:

I focus on online resources here to eliminate any excuse that delays getting started. If you are reading this, then you have online access.

If you know of valuable resources, including books, not compiled below, please link to them in the comments.

- Charlottesville organizers ask you to take these 8 actions, from Medium

- Cultural Appreciation: 7 Women on Embracing Their Heritage Through Their Style, from Teen Vogue

- Overcoming Implicit Bias and Racial Anxiety, from Psychology Today

- Self-care as a form of resistance, from The Seattle Globalist

- Study Shows Mindful Meditation Helps Reduce Racial Bias, from Yes! Magazine

- This BLM Meditation Can Help People Cope With The Tiring Cycle of Oppression, from The Huffington Post

- What Black Lives Matter Organizers Are Doing To Fight White Supremacy At Every Level, from Bustle

- When black death goes viral, it can trigger PTSD-like trauma, from PBS NewsHour

- 4 Self-Care Tips for People of Color When Racial Violence Is All Over the News, from Teen Vogue

- 9 Way Non-Black Folks Can Show Up for Charleena Lyles, from The South Seattle Emerald

- 26 Ways to Be in the Struggle Beyond the Streets, from Piper Anderson, Kay Ulanday Barrett, Ejeris Dixon, Ro Garrido, Emi Kane, Bhavana Nancherla, Deesha Narichania, Sabelo Narasimhan, Amir Rabiyah, and Meejin Richart

Resources for White Americans

White Americans get their own section not just because white people created this system of inequality but also because too many don’t lift a finger to oppose it. Literally. Most White Americans – 67% – refuse to even click to share race-related articles on social media.

White Americans get their own section not just because white people created this system of inequality but also because too many don’t lift a finger to oppose it. Literally. Most White Americans – 67% – refuse to even click to share race-related articles on social media.

As I have written before, “there are no doubt complexities that come with White Americans working for racial justice. White privilege can lead to a chronic case of undiagnosed entitlement, creating poor listeners, impatient speakers who talk over others, and people unaccustomed to taking orders. Nevertheless, the movement for racial justice needs more White Americans to get involved.”

For White Americans, your list of resources has been ready and waiting for you since 2015: Curriculum for White Americans to Educate Themselves on Race and Racism – from Ferguson to Charleston

Here are more thought-provoking pieces published since 2015, a list which relies heavily on the work of Ijeoma Oluo and starts with this short video by Janaya Khan:

So You Want To Fight White Supremacy, from The Establishment

So You Want To Fight White Supremacy, from The Establishment- Stop Condemning My Bitterness, Start Condemning The System, from Medium

- White People: I Don’t Want You To Understand Me Better, I Want You To Understand Yourselves, from The Establishment

- Whites Only: SURJ and The Caucasian Invasion of Racial Justice Spaces, from The Establishment

- White People Will Always Let You Down, from The Establishment

- 6 Signs Your Call-Out Isn’t Actually About Accountability, from Everyday Feminism

- 9 Phrases Allies Can Say When Called Out Instead of Getting Defensive, from Everyday Feminism

Racism is so pervasive that it infects pretty much every facet of our world. This reality can be overwhelming but, on the flip side, it makes it relatively easy to find a struggle to join. Find a racial disparity that overlaps with your sphere of influence – your neighborhood, the school system, the workplace – and dedicate yourself to eradicating it.

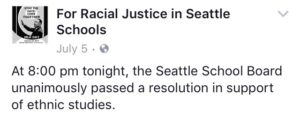

To take on egregious racial disparities in my school district, I joined the movement to bring ethnic studies to Seattle, courses with well-documented benefits for both students of Color and white students.

To take on egregious racial disparities in my school district, I joined the movement to bring ethnic studies to Seattle, courses with well-documented benefits for both students of Color and white students.

There’s likely a group already formed that you can join. In Seattle, the community created the #BlocktheBunker campaign to successfully fight off the city’s attempt to build an extravagant new police station. The #NoNewYouthJail movement continues to fight incarcerating youth, a practice that dramatically increases the chance of future incarceration.

And when there isn’t an existing group, you can still take racial justice into your own hands.

Natasha Marin initially used a Facebook page, now a website called Reparations, through which people of Color can make requests and white people can offer services and goods.

Terri Kempton and Layla Tromble created White Nonsense Roundup, to “round up” the rampant racism perpetuated by White Americans on social media.

#WeNeedDiverseBooks formed in part in response to an all-white, all-male panel of children’s book authors at the 2014 BookCon.

Alica Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors founded #BlackLivesMatter in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer.

The point is: do something!

Step 11: Repeat These Steps Until Anti-Racist Action Is an Integral Part of Your Life

I have been teaching about race and racism for nearly 20 years, but every year – without fail – I come away with a new insight. We are never done learning, especially when the world keeps shifting.

When you finish reading step 11, start over. Repeat the process. There’s a good chance you will find something in all the voices that make up this guide that you didn’t notice – or weren’t ready for – the first time around.

Beverly Daniel Tatum uses the analogy of a spiral staircase when discussing our racial journeys, which are far more circular than linear: “As you proceed up each level, you have a sense that you passed this way before, but you are not in exactly the same spot.”

As you climb, remember: the goal of this guide is not awareness. It’s action.

For more ideas on working for racial justice, check out the Roads to Racial Justice series.